Nadje Al-Ali and Deborah Al-Najjar, editors, We Are Iraqis: Aesthetics and Politics in a Time of War. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2012.

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this book?

Nadje Al-Ali and Deborah Al-Najjar (NA and DA): The idea for this book first emerged in 2006, when Iraqis were generally portrayed either as passive victims or as perpetrators of horrific violence. In the midst of an ongoing humanitarian crisis and the violence, destruction, killings, and widespread sufferings inside Iraq, we did not hear the voices of contemporary Iraqis. While media and academicians centered on suicide attacks, Islamist militias, occupation forces, political leaders, political processes, and the oil economy, we did not find in-depth and creative explorations of and engagements with the rich and diverse forms of cultural expressions that have been part of historical and contemporary Iraq. We also wanted to stretch the prevalent discussions about “resistance” and explore non-violent creative ways to resist, not only the occupation, but also other forms and sources of violence, such as those linked to insurgent groups, sectarianism, patriarchal structures, and criminal gangs.

We wanted to create a cutting edge piece of work on Iraq by fiction writers, poets, artists, bloggers, activists, and academics of Iraqi descent. We also wanted to produce an anthology that would include the multiplicity of Iraqi voices inside Iraq and in the diasporas.

At the same time, we were motivated by the dearth of commentaries or published works by Iraqis themselves. We wanted the book to both reflect and reflect on the artistic integrity and breadth of Iraqi cultures. The Iraq wars have affected the culture and the people in ways that are ineffable. Art and poetry sometimes provide us with reprieves and salves in a way that other modalities do not.

[Maysaloun Faraj, "Ahlam: Kites and Shattered Dreams" (2011). Image

courtesy of Ava Gallery, copyright Maysaloun Faraj.]

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does it address?

NA and DA: The book stretches the idea of who is an Iraqi and what it means to be an Iraqi. Aside from challenging the victim-perpetrator trope that characterizes much of the current engagement with Iraq, we also wanted to break out of the inside-outside dichotomy, without glossing over differences in terms of people’s experiences inside Iraq and in the diaspora.

The contributors are art historians, visual artists, poets, filmmakers, photographers, and performance artists, as well as academics. They work in plural domains and with a variety of media for their artistic endeavors. Each person had a personal story to tell as well as a larger articulation about their relationship to Iraq, homeland, and familial ties. Topics and issues include diaspora politics, a critique of sectarianism, experiences with depression and separation of families, and violence inside Iraq, as well as poetic testimonials that address familial desires, the desire for tranquility, and freedom from the tyranny of daily bombings. The book is firsthand accounts of the realities of Iraqis inside Iraq and those living in various diasporas.

J: How does this work connect to and/or depart from your previous research and writing?

NA and DA: This book aligns nicely with previous work, in that the book has contributors speak for themselves. As an anthropologist and a cultural studies scholar, we both appreciate textual analysis and the plurality of interpretations that might come from “reading” various cultural texts. Yet we both are departing from our conventional academic writing and academic expectations about scholarship and discourse analysis to produce a book that is a testimony to a heritage, a geographic history, and a desire for community. We are also both, for the first time, engaging with the visual in addition to texts and oral testimonies and accounts.

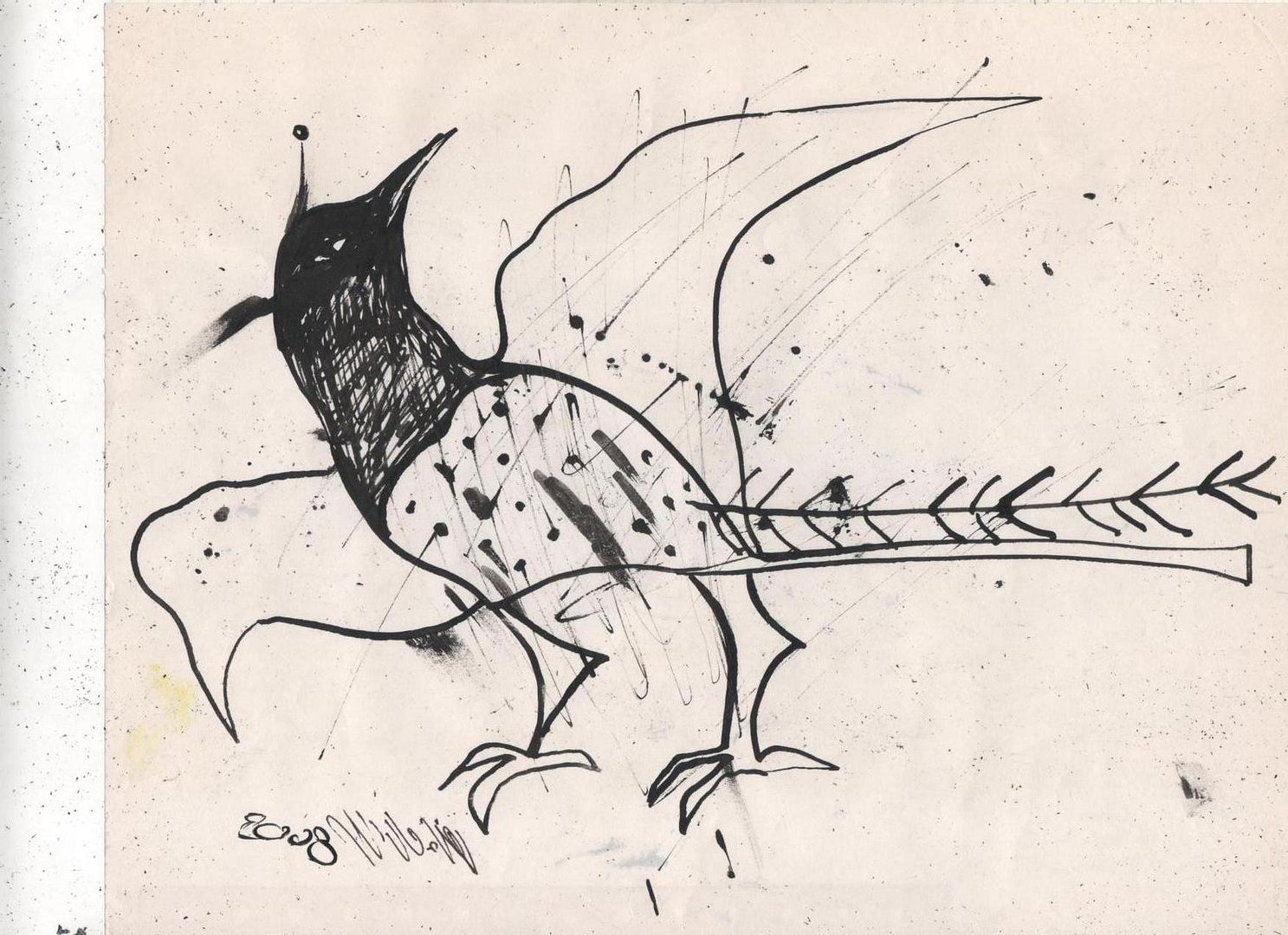

[Hana Mallah, from the series "Birds" (2005). Image courtesy of the artist.]

However, for Nadje Al-Ali, the book also represents a major departure, as all her previous publications were more specifically focused on women and gender issues. Her work on Iraq to date comprises a modern history of Iraqi women, a co-authored book on the impact of the occupation on women and gender relations in Iraq, and research on the Iraqi and Iraqi-Kurdish women’s movements, as well as publications on the political mobilization of Iraqi women in the diaspora.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

NA and DA: We hope that various communities of artists, activists, and academics would read this book. We also hope the general population might engage the book. In the first instance, we had a western-based readership in mind given that we are both based in two western contexts—the US and the UK respectively—and are familiar with stereotypes about Iraqis and Middle Easterners more widely. However, as we developed this project and the book, we also realized that we are writing against the assumption of what it means to be an Iraqi amongst many Iraqis themselves, and that we were trying to open up and stretch notions of Iraqi identity and culture. Given that we are both involved in activism, we were also hoping that the book would reach beyond an academic readership.

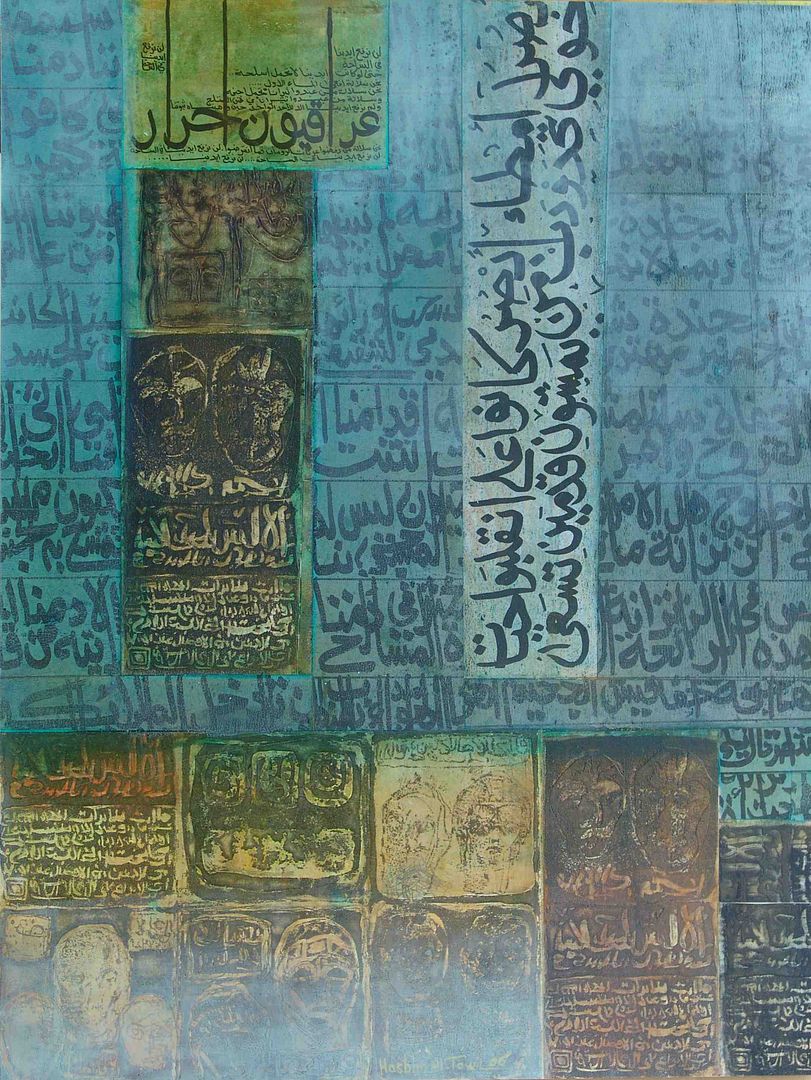

[Maysaloun Faraj, "Al-Rahman, Al-Rahim" (2011). Image

courtesy of Ava Gallery, copyright Maysaloun Faraj 2011.]

J: What other projects are you working on now?

DA: My dissertation manuscript, “Around 1991,” examines cultural texts 1950-2003, as they perform a history of Iraq in relation to the first Gulf War. I argue that the trope of the whore and the rape victim in literary, cinematic, and performance work become both anti-war strategies and evidence of racial/sexual trauma.

NA: Over the past two years, I have focused on working with Iraqi academics and Iraqi women’s rights activists to increase the capacity for empirical and evidence-based research. I have coordinated two qualitative research projects, one based in Baghdad and one in Erbil, to study the specific problems and challenges faced by female academics in Iraq. During this period, I have also organized and chaired a number of workshops and seminars with the aim of increasing research capacity amongst Iraqi academics, and to introduce qualitative research as well as women and gender studies as an academic discipline. It has been fantastic to be able to meet and work with a number of Iraqi academic and activists, and we are currently working on Iraq’s ever first Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) shadow report.

J: How does your examination of the relationship between power and creativity problematize Western notions of women`s agency in the Arab world?

NA and DA: Our book does not participate in the discourse on Arab women’s agency per se, except to debunk the simple binaries that create false splits between feminism and anti-Arab/anti-Muslim culture. We Are Iraqis does not create a gender ideology around creativity and agency. Justice for all Iraqis comes in the courageous willingness to address social, economic, and cultural inequities. Artists have expressed their sorrow and their political orientation and analysis with honesty and emotion. Their views are diverse and cannot simply be categorized along gender, ethnic, or national lines.

[Hashim Al-Tawil, "Eulogy to Saadi" (2011). Image courtesy of the artist.]

However, we also recognize that artistic productions and creative coping strategies are gendered, as are all other aspects of social, political, and economic lives. Irada Al-Jabbouri’s voice and piece, for example, provides a moving illustration of the significance of female writers in Iraq. In her writings, Jabbouri often engages with gender issues, and her female characters are frequently struggling with and against social norms and restrictions. Meanwhile, Hana Malallah’s artwork and her history of teaching art in Baghdad defy the idea that art production remains a male domain. Many of our contributors are, of course, female, and whether based in the diaspora or inside Iraq, are actively challenging and problematizing prevailing Western notions of Arab women’s agency through their own creativity and through their representations.

Excerpts from We Are Iraqis: Aesthetics and Politics in a Time of War

Irada Al-Jabbouri: Identity of the Numbers

I study the numbers...I search for the faces of the killed...I try to find out the identity of no. 530, or no. 3, or no. 200, or 29, or 2773....I ask for the number of our neighbor’s young son who left the house one day and did not come back. His family only happened to find his swollen dead body, days later...piles of bodies waiting for someone to identify them.

What the number can’t tell you is that Saad was twenty-two years old, he loved the Barcelona football team, and he used to support the Talaba Iraqi team. He used to love dibs and rashi (date syrup and tahini, usually eaten for breakfast). He used to dream that the day would come when the girl who studies at the Teachers’ Institute would return his look—everyday she passed by the shop he worked in. The number can’t tell you that Saad’s mother has worked in the salt factory for years and that her whole life has been nothing but hard labor. She worked to support Saad, his two sisters, Nour and Duniya, and her husband who has been unemployed since the beginning of creation—it seems...the number can’t talk about a woman living a miserable, exhausting life, enduring the anger of her domineering husband, his irresponsibility and aggression toward her, just for the sake of Saad and his two young sisters...the number is not able to describe the nights and days that Saad’s mother watched him growing up, dreaming that her patience would produce a self-reliant, independent young man whose children would make her happy—she would hug them until her years-long weariness melted away. The number doesn’t express how she searched for him, or the horror, or her grief at losing him, or her anguish at not finding answers to her questions; why did they abduct her son, why did they torture him, why did they kill him...They have stolen her only hope...the number cannot describe the empty look that has become Um Saad’s identity...Saad, who ceased to be, whose enthusiastic support of the Barcelona team will never be heard again, and who will never see the girl from the institute return his look as she goes and comes to college.

***

Wafaa Bilal: Invisible Mirror-Aggression and the Thumb-Generation Response

The project, which took place at Chicago’s Flat File Galleries in May and June 2007, was conceived as a way to provoke Americans to consider the technologically remote and removed nature of modern warfare, where someone sitting behind a computer console in Colorado can drop a bomb on someone in Iraq. I saw just such an image on the TV news, where the young female soldier in question said she had no remorse about the killing as she was just following orders. My brother Haji was killed by a US bomb at a checkpoint outside our hometown of Kufa in 2004. The bomb was preceded by an unmanned drone—piloted remotely by someone perhaps very like this woman in Colorado. So I conceived of Domestic Tension, informally called “Shoot an Iraqi,” as a commentary on the nature of modern technological warfare. The project also came out of my intense need to connect my life in the comfort zone of the United States to the terrors and sorrows of the conflict zone in which my family and so many others are living out their daily lives.

In addition, Domestic Tension was meant to highlight the dehumanizing effects of occupation and distant war on the citizens of the United States, who have been mostly shielded from the actual horrors of their government`s campaign in Iraq. Our lives go on without a care in the face of the devastation and destruction being caused in our name. I wanted to impose questions on viewers and participants. What would it be like if one had to actually face down and attempt to "kill" his or her own Iraqi target? What kind of crisis might that provoke? I was posing these questions not only to agitate but also as an attempt to humanize the conflict.

I did not want to create another art project sheltered by the aura of the gallery. Nor did I want to do another street protest that would preach to the converted and alienate people more than engage them. I wanted a project that would enter people’s homes and workplaces, one that would arise unexpectedly in the flow of their daily lives and prod them to think of people in Iraq under fire at a moment they had not expected or prepared to do that.

***

Maysoon Pachachi: A Film-Training Project for Young Iraqis

In June 2003, Kasim and I sat in Stones, a café in Ramallah, stirring our coffees, as a shaft of warm afternoon light fell across the table, and talked about Iraq. We didn’t know what we could do that would be of any use. We weren’t doctors, engineers, or politicians. Most people we knew thought you should wait to see what was going to happen. But we felt that if we were going to do anything, then we had to start now.

That afternoon, encouraged by our experiences in Palestine, we decided to set up a free-of-charge film-training center in Baghdad. We would offer basic short courses in camera, sound, lighting, editing, and documentary and short fiction filmmaking. A few months later, Kasim traveled back to Baghdad to see his family for the first time in thirty years. While he was there, he talked to all sorts of people about our idea. The response, especially from young people, was overwhelmingly positive. In Iraq, it had long been impossible to make films free of government control; and thirteen years of sanctions meant there had been no film stock, no spare parts for film cameras, no labs or new video cameras, and no digital technology. Even film students and their teachers at the Academy of Fine Arts had had little opportunity to make films or handle cameras.

Maybe young people were so enthusiastic about the idea because they’d been deprived of making films for so long, or maybe they were excited by the sudden access to so many satellite TV stations, or maybe they thought it was a good way to make a living. This was a generation that had only known dictatorship, continuous war, sanctions, and social disintegration, and now there was a military occupation and extreme political and criminal violence. They were traumatized and silenced. Maybe they also saw making films as a way, finally, to be able to tell their stories and to put their thoughts and feelings on the screen for the rest of the world to see. Certainly, if we could, we wanted to use whatever skills and experience we had to help them to do this.

[Excerpted from We Are Iraqis: Aesthetics and Politics in a Time of War, edited by Nadje Al-Ali and Deborah Al-Najjar, by permission of the editors. Copyright © 2012 by Syracuse University Press. For more information, or to purchase this book, please click here.]